Corrosion – A $3 Trillion Problem!

Perhaps one of the most significant discoveries of recent times is a way to stop rust permanently. This blog is the story of how that happened.

The Original Goal

After selling a contracting business about 15 years ago, we set about finding a way to build high-quality housing in a factory environment. We needed cement that would set rapidly enough to be applied on a moving assembly line and cure fast enough to lift and put on a truck at the end of the line.

A book written by a scientist at Argonne National Labs talked about a cement they developed for the Department of Defense designed to shield radioactive waste. The product was an acid-base cement that was extremely strong. Best of all – it would set in minutes. So, it seemed like this cement might work for our purposes.

Upon visiting Argonne, we learned a few things. First, the government already had its solution and did not need to fund further research. What the government did with the cement is classified, but since it was developed to shield nuclear waste, and the product’s user was the Savannah River Project, the location where the United States makes nuclear weapons, it was easy to guess how they used the cement.

The Additional Research

Argonne was desperate for a new sponsor. So, in exchange for sponsorship of another year of research, Argonne gave us a license for any applications for the cement that were not related to nuclear waste. Immediately we hired eight scientists and started work on engineering the cement for our specific application – and perhaps a few other applications.

One day a potential customer asked if they could use the cement for fire protection. Since we were a research facility, we tested it. To test this, we poured the cement (before we learned how to spray it) on a piece of steel that immediately got knocked off the table. The cement fell on the floor. As a result, we threw that piece of steel in the scrap bin and started over.

The Accidental Observation

This seemingly unimportant event would be a pointless story, except I married the most observant woman I’ve ever known! A few months after the incident, we drove into the back of our plant, and Sandy asked about a piece of steel in the scrap bin. She wanted to know why all the steel in the scrap bin rusted, but one piece looked new. Curious, we determined that it was the piece upon which we had done the cement test – the piece that fell to the floor and was discarded.

From there, we wondered if there was something unusual about the cement. And in looking closely around our facility, we discovered that all steel that the cement had touched wasn’t rusting. For the next couple of weeks, the scientists would point out new areas to each other. What sticks with me to this day was that none of the geniuses in that research group, and most of them had IQs well into the genius range, could see the effect the cement was having on steel. However, a sharecropper’s daughter with no formal education could see it.

The Intentional Focus

In addition to our other research, we spent the next eleven months doing two things.

1- We tried to make that steel panel rust. We made our own salt spray chamber. Seawater was trucked in from the beach. Scientists hung UV grow lamps to create sun and salt exposure. Quite simply, the bottom line was that we could not make that carbon steel panel rust.

2- We tried to find out what was causing this amazing behavior. We completed x-ray diffraction five different times. The scientists kept reporting that they saw nothing there. It was just plain steel.

Scientific Method Isn’t Failure, It’s Innovation

After months of failing at both tasks, we couldn’t make the steel rust, and we couldn’t figure out why it would not. Then, finally, one of our scientists posed an interesting question, “You know, surely the product of an acid and base reaction is a crystalline structure. But what if it is not?” To which I responded, “What are you telling me?”

The answer was that if the product of the cement was not crystalline, then the x-ray diffraction techniques we were using would not identify it. Essentially, this is because x-ray diffraction detects crystal structures.

We Needed To See What We Had Discovered

We were left to question, what test might identify whatever was on the substrate? It was Vadym Drozd that suggested we do Scanning Electron microscopy in cross-section. Vadym explained that this might show up whatever was on the surface of the steel.

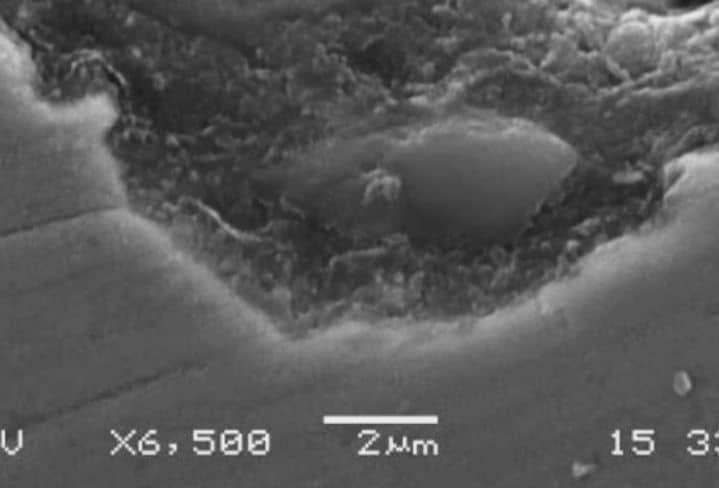

Below is the photo of that very first Scanning Electron Microscopy of EonCoat. A large portrait of it hangs in our offices. It was a world-changing event.

What you see in the photo is steel at the bottom of this slide and the alloyed layer of magnesium iron phosphate chemically bonded to that steel. The layer of magnesium iron phosphate is inert – meaning it insulates the steel below and will not react with the elements. This observation changed everything in the world of corrosion protection. But, as you will learn below, it changed a lot for me, too.

Remember that our objective was to build housing in a factory. That goal was why we had rented 100,000 square feet of space in Wilson, NC. However, the discovery led to some difficult choices. We had a plan, and it seemed like a good one. We had invested a lot of time and money in that plan to build housing that would be both high quality and affordable. Now we owned an amazing technology and needed to decide what to do with it.

We held a meeting with the scientists to get their ideas on how to proceed. It was clear that we didn’t have the bandwidth or the wealth to pursue all the technology we now owned. So something had to go on the back burner. Everything but one thing needed to go on the back burner. My favorite was not to pursue this cementitious coating but one of the other discoveries this amazing group had made. Ultimately, one of those brilliant scientists made the case that changed my mind.

This gentleman said, “Tony, a guy like you who has already sold a large business could have retired a while back. But, to work the way you do, you have to care about something bigger. It’s about making a difference. We don’t know for sure yet, but there is a good chance that we can permanently solve the worldwide misery of corrosion. The plague of rust is a burden of $3.6 trillion a year on society. That is nearly $50 a month for every man, woman, and child on the planet. This money is completely wasted. Think about the better ways that money could be used.” This transformative statement was the argument that sold me.

The Growth and Development of EonCoat

That conversation led me to fund the development of how to apply this technology in a convenient and cost-effective manner – we now spray it like paint. The argument sustained me through many heartaches where things didn’t go as we expected. But ultimately, now, all these years later, EonCoat is in use on every continent, and we are on the road to fulfilling the objective of ending rust permanently.

I’m grateful for all the support and guidance from customers who have not only tested the technology, written about it, and used it to solve their own corrosion problems but also helped us solve problems that led to more patents.

If you enjoyed our story thus far, we would welcome you to join us and be part of the remainder- let’s end rust in our lifetime.

Tony

Ready to Learn More About EonCoat?